Why You Should Strongly-Type Your Localizations with Swiftgen

To start off this story, you will see a very basic code example which includes a few issues. Together we will improve the code snippet and eventually create a sophisticated solution.

Even tough this story uses SwiftUI in this story, it is not the main scope, and only used for simpler code snippets. The concepts apply to any kind of Swift projects available, including UIKit/AppKit interfaces or even command line tools.

Issues hidden in plain sight.

Take a look at the following example of a view showing a call-to-action message and the action button:

struct MyView: View {

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Tap on the button \"Tap me!\"")

Button("Tap me!", action: { /* do something */ })

}

}

}

If you use this code snippet in a SwiftUI app it will work fine and the call-to-action fulfills its purpose: it tells the user to tap on the button.

Some developers would stop thinking further about this code and keep going with the project, but you might have already noticed a potential issue: Changing the button text will lead to inconsistency!

struct MyView: View {

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Click on the button \"Tap me!\"")

Button("I'm a button", action: {})

}

}

}

The first main issue is code duplication, or specifically duplicated strings. When we change the label of the button, we also have to change the words in the message.

As an initial solution we decide to create a small static constant, which can be used in both cases.

struct MyView: View {

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text("Click on the button \"\(Strings.tapMe)\"")

Button(Strings.tapMe, action: {})

}

}

}

enum Strings {

static let tapMe = "Tap me!"

}

This easy change already improved our code on two ways:

- no more duplicate strings in our code base, and

- both the

Textand theButtonare now guaranteed showing the same value.

The Story Continues…

Your project grows and you keep adding more views, and eventually get to a finished version. The one you are proud to share with the world. Soon later you realize: “I have to translate the app, so more humans can use it” and you start looking into iOS/macOS localization techniques.

Fortunately this is quite easy to implement using the NSLocalizedString macro/function, and so we can change our

constant to apply localization.

enum Strings {

static let clickMe = NSLocalizedString(

"Tap me!", // <-- lookup key and default value

comment: "Label of button which calls for action")

}

What NSLocalizedString does under the hood is straight forward: we pass it a string which is used a lookup key in the

localized .strings file. If a translation is found, it gets returned, otherwise the lookup key acts as a default

value.

Additionally you create the relevant Localizable.strings file with the localized strings for the newly added language.

As I am from Austria, I’ll go with German as the second language for this story.

// Localizable.strings (German)

/* Label of button which calls for action */

"Tap me!" = "Tipp mich!"

Perfect. Once again you run your application with a different application language, and NSLocalizedString uses the Tap

me! as a key to lookup the translation Tipp mich!.

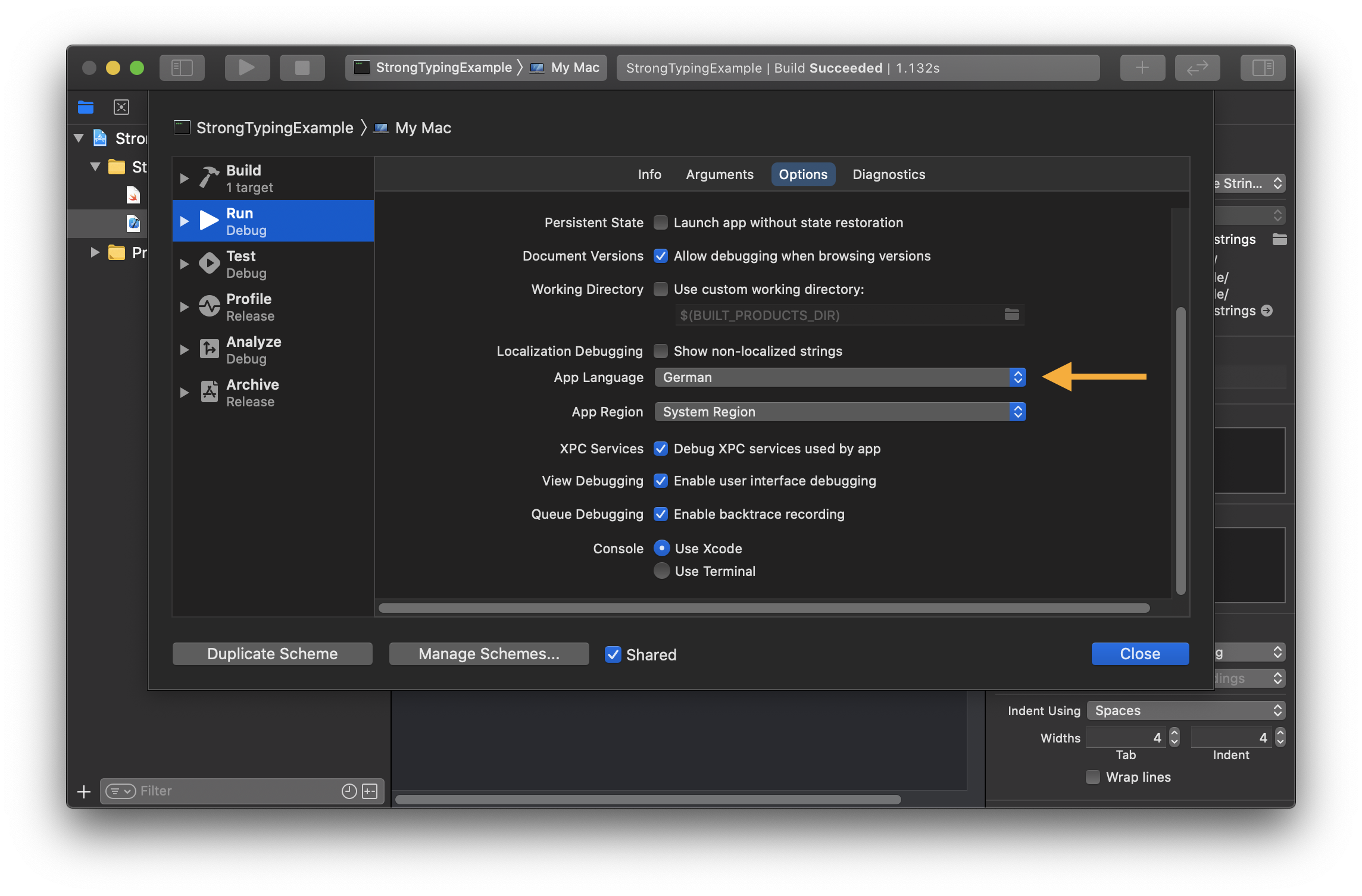

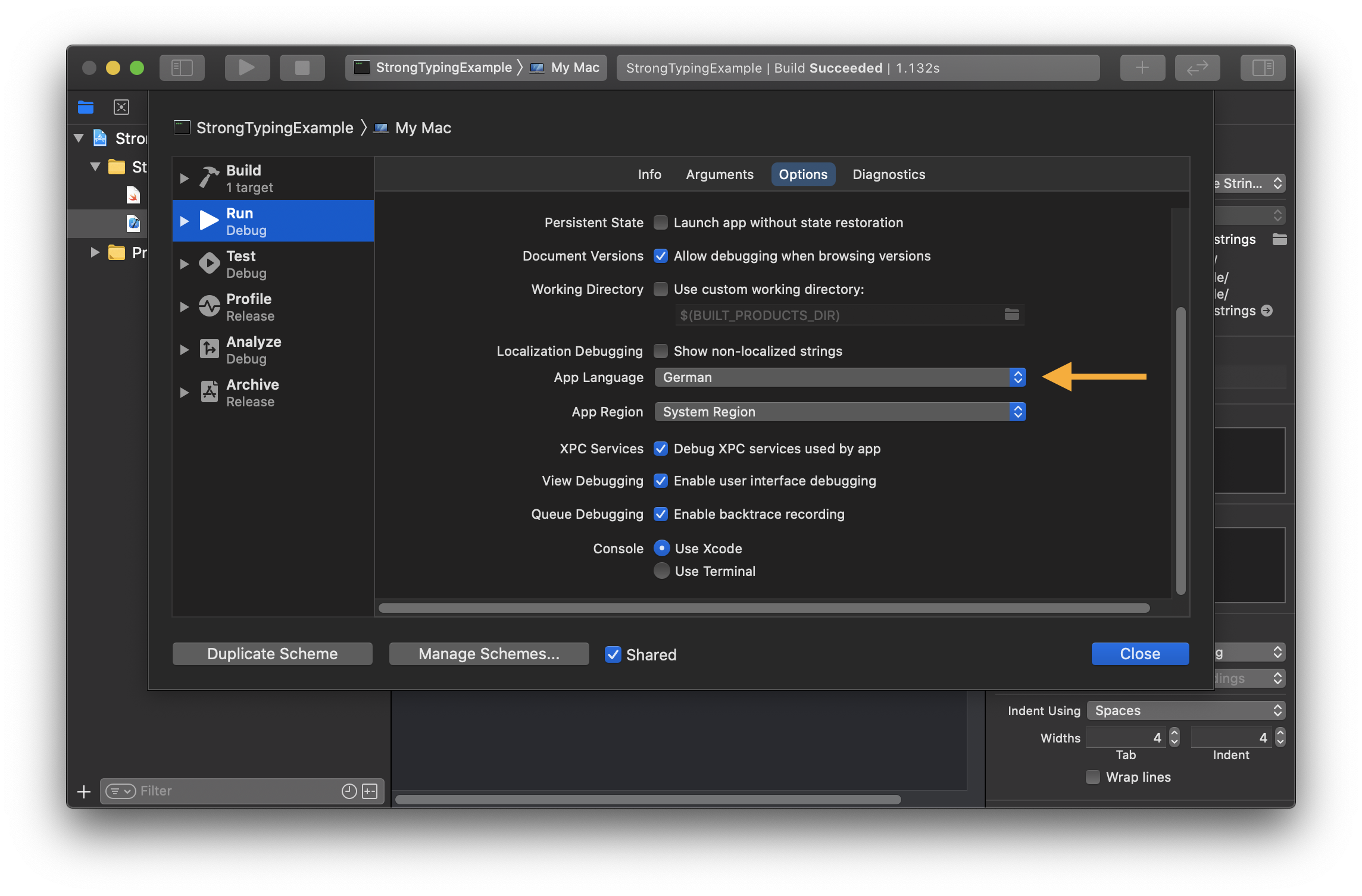

Quick Tip: You can change the current runtime language in the schema seetings

Quick Tip: You can change the current runtime language in the schema seetings

Unfortunately this introduced the same issue we defeated earlier: even tough the link between UI and the String constant is secured by compile-time safety, the link between our constant and the localization resource is not guaranteed!

This means, if we change the lookup key name in the NSLocalizedString call (e.g. to Please tap me!), it won’t find the

mapped translated string anymore. Even worse, we won’t notice it, as the build process does not fail (due to the default

behavior of not translating, if not found).

The easiest solution is introducing static keys, but we do not want to show a static identifier to the user in our UI. Therefore we need to add a value parameter, which now provides the original string as the default value.

enum Strings {

static let clickMe = NSLocalizedString(

"call-to-action.button.text", // <-- only key

value: "Tap me!",

comment: "Label of button which calls for action")

}

To reflect our new changes to the localization file, you also change the localized .strings file to match the key:

// Localizable.strings (German)

/* Label of button which calls for action */

"call-to-action.button.text" = "Tipp mich!"

These few changes already fixed the issue. But we are still not quite there yet. The linking between the constants and the translation files are still loose and far from being guaranteed.

Before going further down the improvement road, we need to add our message to the constants too. As it inserts the button text using String interpolation, but our translation files are only static strings, we need to adapt the code:

Text(String(format: "Click on the button \"%@\"", Strings.clickMe))

We use String(format:) which takes a format/template string as the first parameter, and replaces all format specifiers

(e.g. %@) with the variadic parameters.

Quick Tip: Format specifiers are standardized for most programming languages. You can find a full list in the Apple Documentation.

Add another static key with the translated value to the Localizable.strings file and declare it as a constant in our enum:

// Localizable.strings (German)

/* Label of button which calls for action */

"call-to-action.button.text" = "Tipp mich!";

/* Format string for the call to action message */

"call-to-action.message.text" = "Tipp auf \"%@\"";

struct MyView: View {

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text(String(format: Strings.message, Strings.clickMe))

Button(Strings.clickMe, action: {})

}

}

}

enum Strings {

static let message = NSLocalizedString(

"call-to-action.message.text",

value: "Click on the button \"%@\"",

comment: "Format string for the call to action message")

static let clickMe = NSLocalizedString(

"call-to-action.button.text",

value: "Tap me!",

comment: "Label of button which calls for action")

}

Swift is a language with strong typing and the compiler does great work helping us finding common issues. It also helps us to think less about the preconditions of certain code, such as the required parameters for a function call.

As NSLocalizedString and String(format:) use string-based APIs, this type safety does not apply to them. Even worse

it can lead to crashes when used incorrectly (by personal experience with os_log, which also uses format strings).

Luckily, we are skilled programmers, and can wrap the usage of String(format:) in a function with a single parameter,

to reduce the looseness of the link:

struct MyView: View {

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text(Strings.message(Strings.clickMe))

Button(Strings.clickMe, action: {})

}

}

}

enum Strings {

static let messageFormat = NSLocalizedString(

"call-to-action.message.text",

value: "Click on the button \"%@\"",

comment: "Format string for the call to action message")

static func message(_ p1: String) -> String {

String(format: messageFormat, p1)

}

static let clickMe = NSLocalizedString(

"call-to-action.button.text",

value: "Tap me!",

comment: "Label of button which calls for action")

}

What a clean solution 🤩 The constants include all necessary information, which most likely will not need to be edited soon, and the usage inside the view is quite elegant.

As Xcode still does not provide us with a validation tool between our custom constants and the localization files, these mappings need to be created by hand and checked by the developer manually.

Reversing the Direction

So far we have always written our code first, then added the strings to our localization files. Even if we changed the code afterwards, you most likely will define a new constant first and later add the translation in the future too.

Doing it this way sounds like a logically coherent approach… but what if we switch it around? What if we do not need to create the enums, constants, helper functions, etc…. and instead just ask the Swift code completion for available resources? foreshadowing intensifies

Feels contradicting to our previous conclusions, but stick with me. You will love what’s coming next.

Swiftgen

Swiftgen is a code generator for Swift code. It’s main purpose is reading existing data using different parsers (.strings, .xcassets, .json, etc.), combining it with versatile Stencil templates and writing it to compile-ready Swift code… automatically.

With over 7,100 ⭐️ on GitHub (at the time of writing this story) it is already a widely popular project, and with almost 6 years of active development a mature solution.

Their documentation is comprehensive and the getting started guides easy to understand, so here is only a rather quick summary to continue with our use case:

After installation we first need to create a configuration file swiftgen.yml with the following content:

strings:

inputs: en.lproj

outputs:

- templateName: structured-swift5

output: Generated/Strings.swift

As we do not want to define localization by hand in our code, create a Localizable.strings for the default language (in this case it is English), and write down the values previously defined in our constants:

// Localizable.strings (English)

/* Label of button which calls for action */

"call-to-action.button.text" = "Tap me!";

/* Format string for the call to action message */

"call-to-action.message.text" = "Click on the button \"%@\"";

Afterwards run the command swiftgen in the same folder as the configuration file (make sure your path to the

localization folder is correct). It will read our .strings file, and create a strongly typed localization enum in the

Generated/Strings.swift file:

// swiftlint:disable all

// Generated using SwiftGen — https://github.com/SwiftGen/SwiftGen

import Foundation

// swiftlint:disable superfluous_disable_command file_length implicit_return

// MARK: - Strings

// swiftlint:disable explicit_type_interface function_parameter_count identifier_name line_length

// swiftlint:disable nesting type_body_length type_name vertical_whitespace_opening_braces

internal enum L10n {

internal enum CallToAction {

internal enum Button {

/// Tap me!

internal static let text = L10n.tr("Localizable", "call-to-action.button.text")

}

internal enum Message {

/// Click on the button "%@"

internal static func text(_ p1: Any) -> String {

return L10n.tr("Localizable", "call-to-action.message.text", String(describing: p1))

}

}

}

}

// swiftlint:enable explicit_type_interface function_parameter_count identifier_name line_length

// swiftlint:enable nesting type_body_length type_name vertical_whitespace_opening_braces

// MARK: - Implementation Details

extension L10n {

private static func tr(_ table: String, _ key: String, _ args: CVarArg...) -> String {

let format = BundleToken.bundle.localizedString(forKey: key, value: nil, table: table)

return String(format: format, locale: Locale.current, arguments: args)

}

}

// swiftlint:disable convenience_type

private final class BundleToken {

static let bundle: Bundle = {

#if SWIFT_PACKAGE

return Bundle.module

#else

return Bundle(for: BundleToken.self)

#endif

}()

}

// swiftlint:enable convenience_type

If you take a close look at the L10n enum, you might realize: “this looks similar to the constants enum we created earlier!” and you are correct.

After adding this file to our project, we can now delete theenum Strings {...} introduced earlier, and use the

generated L10n instead:

struct MyView: View {

var body: some View {

VStack {

Text(L10n.CallToAction.Message.text(L10n.CallToAction.Button.text))

Button(L10n.CallToAction.Button.text, action: {})

}

}

}

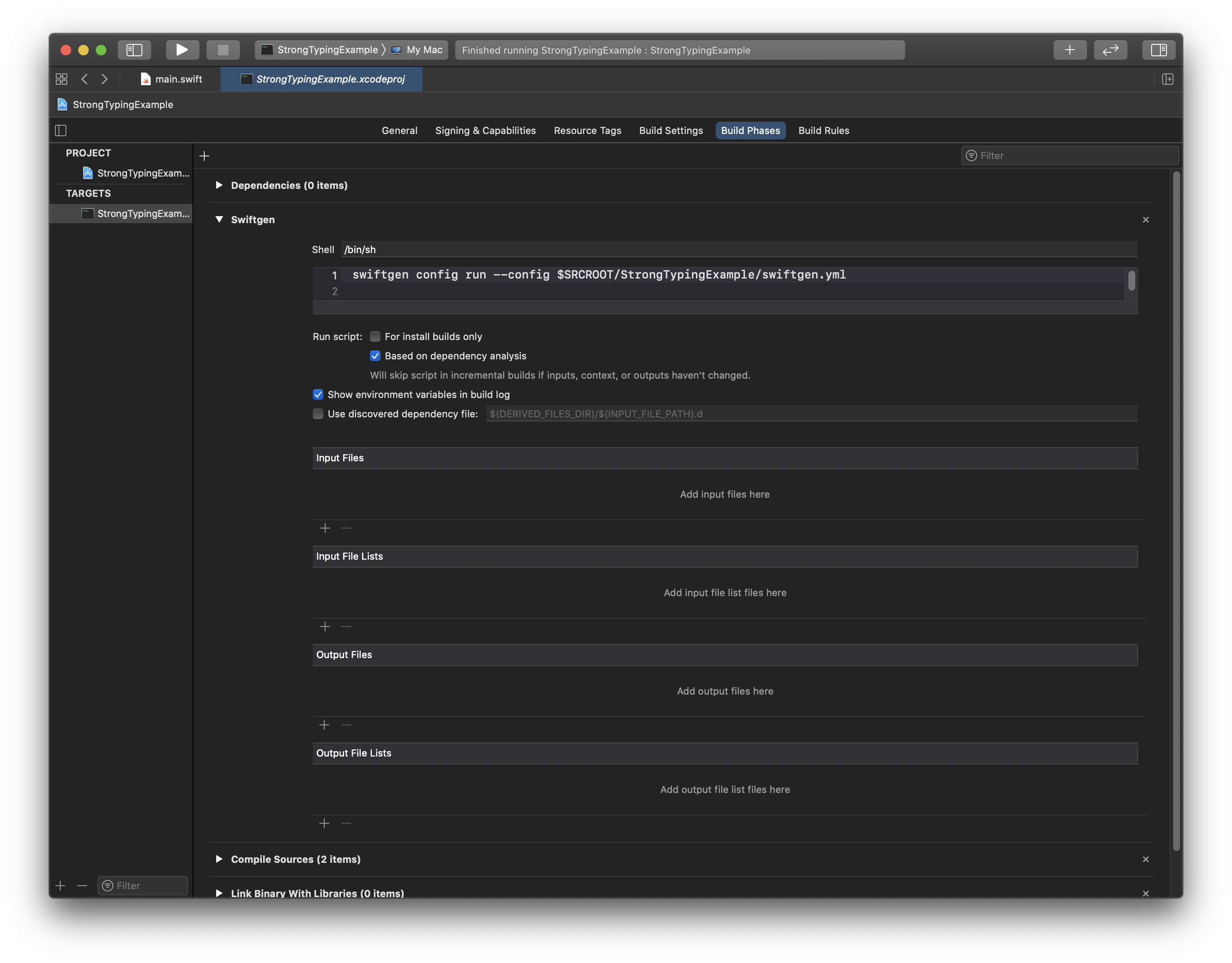

Additionally we can add a build script phase which re-generates the Swift code during build-time, therefore making sure we only access actually given ones.

Quick Tip: the generation script must be run before the “Compile Sources” phase

Awesome! Without further manual work we are able to access our localizations without worrying about keys or parameters… especially when adding new ones 💪🏼

Conclusion

Swiftgen is an automation tool which takes care of generating code to safely access resources, which would otherwise only be available using a String-based API.

In this story we only explored a small subset of the capabilities of this code generator, which can be even more powerful when writing custom templates. To keep the scope of this story nice and tight, this will be explained in detail in another upcoming article, especially with a tutorial on code templates. Make sure to follow me on Twitter & Medium so you don’t miss it!

As mentioned before we would love to have a guarantee that a specific localization key is actually present in the

default language localization file. On the one hand, this is still not fulfilled, especially if the generated code is

outdated and therefore defining different values than given in the .strings files.

On the other hand, in combination with the build script, this is fairly close to how a built-in compiler/code-completion support would work, and therefore if we trust our automation tools… we can trust the mapping.

If you would like to know more, checkout my other articles, follow me on Twitter and feel free to drop me a DM. Tell me about other great build tools for Swift development! You have a specific topic you want me to cover? Let me know! 😃